The best fox hunting happens at night, as Ed Gerren knew. Canines are nocturnal, so the chance of bagging one of the clever creatures increases with the setting of the sun and the onset of darkness.

Ed Gerren had decided he was willing to forgo sleep the night of September 12, 1965, and was still at it long after midnight. At some point, he heard the sound of gunshots splinter the stillness of the night. Assuming it was another hunter, he didn’t pay it much mind.

He had no way of knowing how important the details of that sound would be, because the shots Ed Gerren heard that night were to be the last sounds Deputy John P. Martin would ever hear.

Deputy Martin had arrived at the sandpit, followed by Peggy Carroll and her husband (who was concealed from sight in the floorboard of the Buick,) at around 3 a.m. Peggy had concocted a story about someone throwing rocks at her car and causing damage.

Deputy Martin parked his car, turned on his highbeams, and studied the landscape in the harsh light. Seeing nothing of note, he then got out of his patrol car to investigate further, grabbing his flashlight as he did.

As the hulking deputy began to carefully search the area, his head down, focused on some tracks left by earlier visitors, Vernon Carroll quietly exited the car from the backseat, where he had been lying in wait.

And with him came the M1 carbine rifle that was never far from his grasp. Normally he used it at the sandpit to shoot at cans and such, but tonight he had his sights set on a very different target.

M1 Carbine

Calling out “I want to talk to you a minute,” he leveled the rifle in John Martin’s direction. As Martin heard the words and started to turn, he immediately saw the danger he was in, and drew his service revolver, but was blinded by the headlights of the cars. Even high on Doriden, Vernon Carroll was a skilled marksman, and all six shots he fired found their mark.

Deputy John P. Martin fell face first into the sand, dead.

As the sobering gravity of what they had just done crashed down upon them, the Carrolls began to panic. Somewhere in their drug and alcohol-addled brains, they found the presence of mind to realize they better do something, and quick.

As Peggy stood, paralyzed, Vernon barked at her to get in the Buick and follow him. Terrified, she did as she was told, and Vernon jumped in the deputy’s patrol car. They drove to an area just off Pace’s Bridge Rd and abandoned the car there, then returned to the sandpit.

It took the combined strength of the couple to drag Martin’s 275-lb body across the sandpit, load it into the trunk of their Buick. Unsure of what else to do, they drove.

About six miles away, just off Hester’s Bridge Road in Pickens County, they dumped the body, dragging it, face down across the earth, to a particularly unhospitable, and, they hoped, hidden area.

The Carrolls returned home to their apartment on Poinsett St. and tried desperately to think of a plan that might offer some absolution for their crime, or at least buy them some time.

Vernon’s plan, unsurprisingly, was to run.

His first destination was his girlfriend, Joyce’s duplex, not far away, where he tearfully confessed to her what he had done.

“I killed a man.”

Moved to action by sheer adrenaline, Joyce left with Vernon and the two of them, joined by Peggy, started the process of cleaning the blood from the trunk of the Buick. Vernon instructed them to take the gun, badge, hat, shirt, and wallet he had pulled from the dead man’s body, and dispose of them any way they could.

The girls drove to Paris Mountain, found a sequestered area in the woods, and burned the deputy’s clothing and wallet, as well as the bloody lining of the Buick.

On the way back to Vernon, they discarded the badge, watch, and service revolver in a lake near Furman University. Joyce Chapman then drove her paramour’s wife, to Marietta, and dropped her at her mother’s home. Carroll returned home to Peggy around five o’clock that afternoon, but left again around ten, saying he was going to “Florida or Georgia” to look for work.

In reality, he went once again to Joyce’s, and talked her in to driving him to Virginia. He said he wanted to visit the grave of the grandmother who had raised him before the law caught up with him. We are left to wonder what sort of thoughts filled Vernon’s head during that long drive.

Perhaps, he was seeking some sort of atonement from the one person whose love he felt consistently and powerfully throughout his formative years. Or maybe he was just soliciting sympathy from his girlfriend in an effort to make her complicit.

Whatever the reason, they never made it to that Virginia cemetery. An APB had been sent to the authorities in that area upon learning Vernon was on the lam, and he and Joyce were apprehended in Gate City not long after crossing the state line.

What began on a warm Indian Summer night would end on a frost-bitten, bitterly cold day in the dead of winter. On January 23, the trial of the three conspirators would conclude after five days of deliberation.

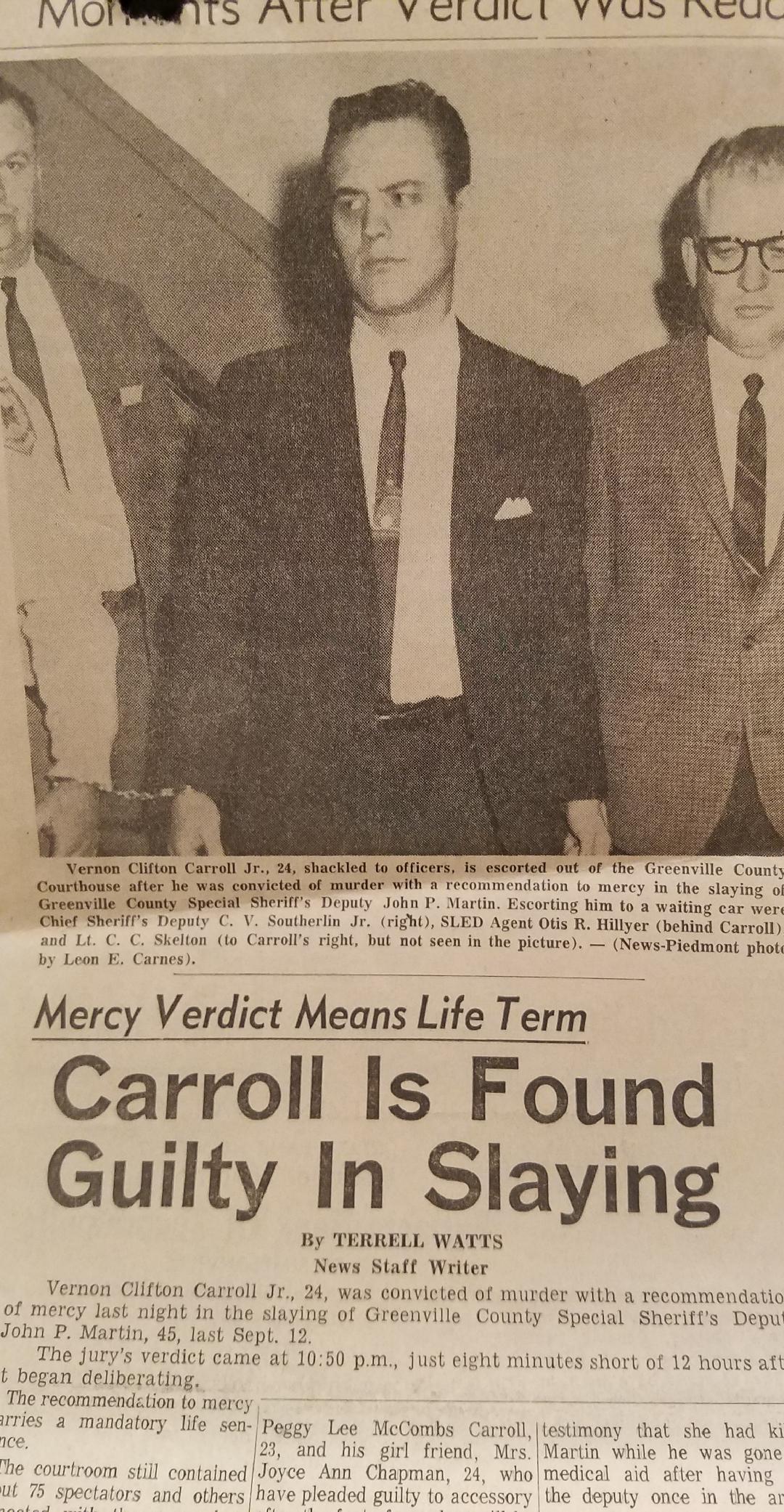

Greenville News

The sleet coating the roads that day did nothing to dissuade hordes of curious onlookers who had packed in the General Sessions courtroom each day for the entirety of the spectacle.

The whole macabre event had mesmerized folks from all around, and it became a sort of morbid social function each day as the gossip and speculation buzzed through the building like an electric current; a festivity that had nothing festive about it.

The scandal would deepen with the testimony of those who were questioned. Details of Vernon’s abuse of the women, both psychological and physical (it was revealed he had once caused an injury to Joyce’s leg that required 30 stitches, and regularly “slapped” Peggy out of frustration) lent an air of credibility to the women who testified they were terrified to go against his wishes.

A sordid tale Vernon had crafted about his wife having an affair with Deputy Martin was dismantled by the judge, who assured the deputy’s distraught widow publicly that there was no indication of anything so untoward and that her husband was “a good man.”

The most disturbing part of the whole scene was, perhaps, the testimony of the psychiatrist from the State Hospital where Vernon had been sent for analysis. The doctor reported that Vernon Carroll undeniably knew right from wrong, and was mentally healthy, as a general rule.

Which meant the only motivation for the senseless murder was killing for the sake of killing.

After twelve hours, the jury returned with a verdict.

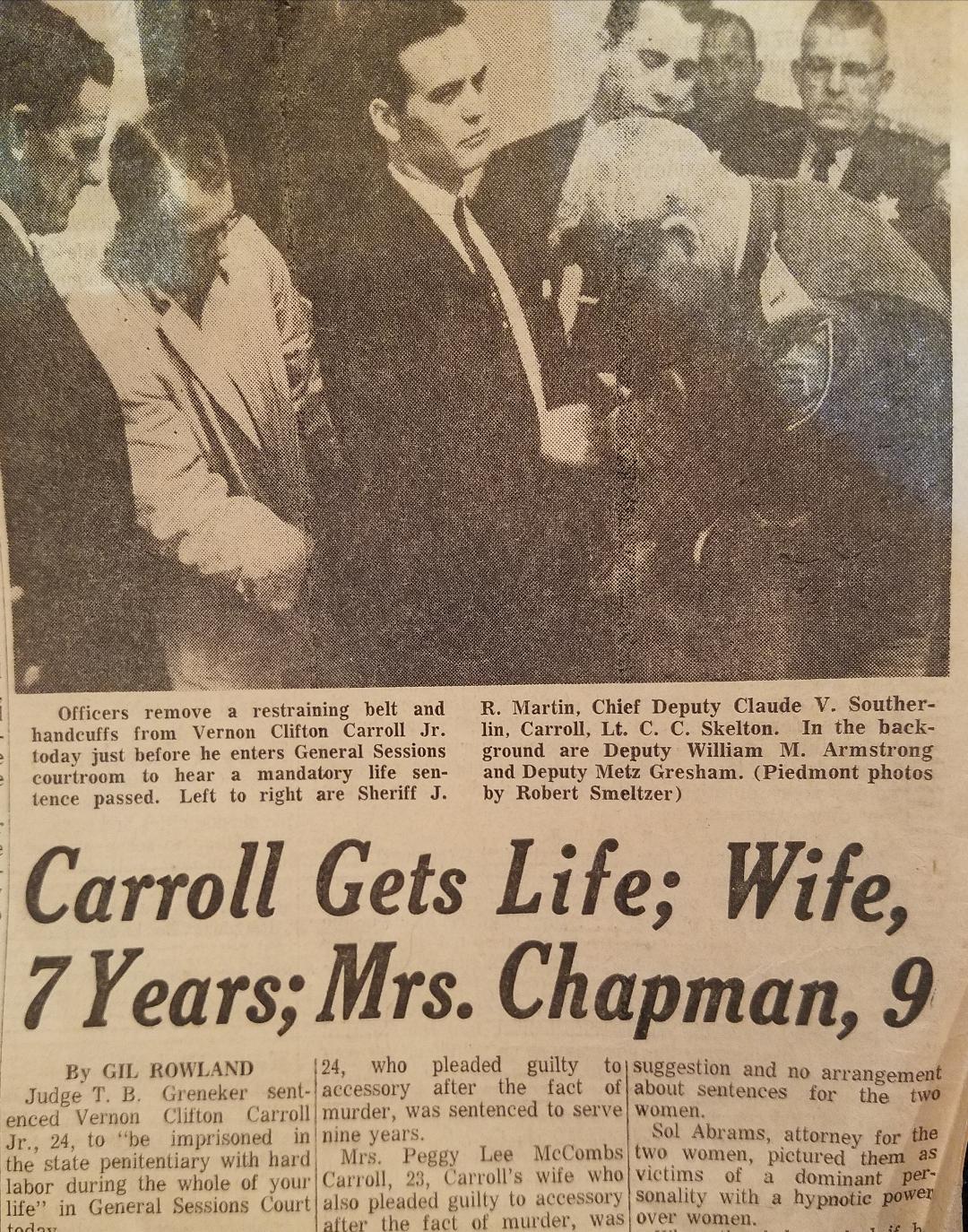

Vernon Carroll would be sentenced with a “mercy” ruling, meaning he would escape the death penalty. The judge handed down the sentence of life in prison at hard labor, addressing Mr. Carroll to say “You got off very lightly.

Greenville News

The jury could have easily convicted you by your own testimony.” Vernon remained stoic for the duration of the trial and sentencing, no emotion surfacing to indicate his state of mind.

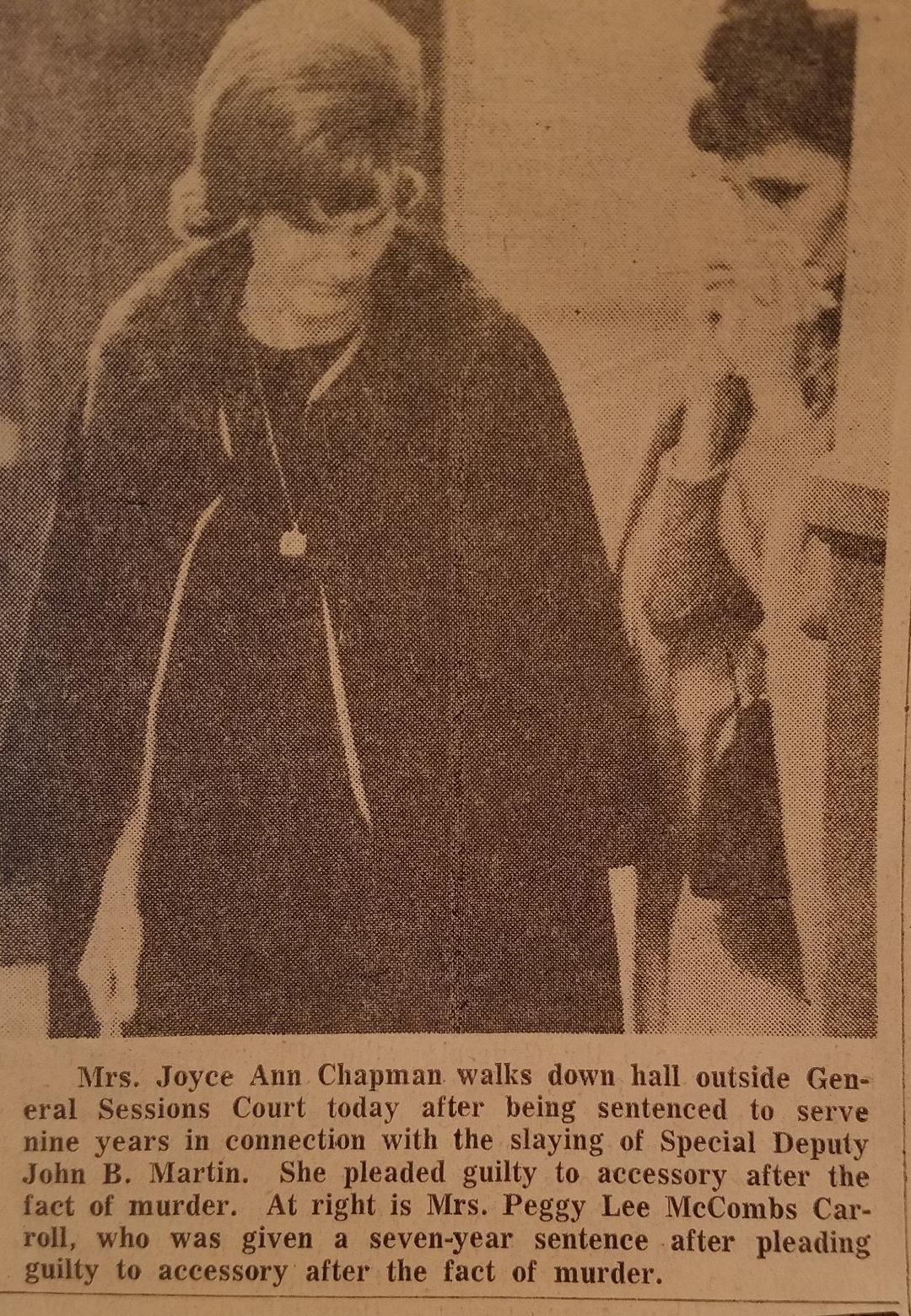

His wife, Peggy, who had testified against him, received a sentence of seven years, and Joyce Chapman, who did likewise, nine years.

After the verdict was handed down, the three defendants were whisked away in handcuffs, led outside into the snowy night through the dense throng of spectators, placed into transport vehicles, and taken to their respective institutions.

The New York Times would cover the story of the sensational small-town murder, as would most media outlets across the nation. Closer to home, I learned about this now-forgotten tale when I discovered a large envelope full of newspaper clippings about the event in my late grandmother’s cedar chest, and became enthralled.

Greenville News

Initially I found it odd that she would have kept so many clippings of the event, and it was some time before I made the connection. Joyce Chapman was my cousin. True to our Southern roots, we never talked about such a dark and seedy story involving our family; “good” people don’t flaunt their skeletons that way.

Instead, we quietly tuck away fragile bits of newspaper and yellowing photographs, pulling them out to peek at now and again, when we’re sure nobody is watching. Family secrets, like Indian Summer, might disappear for a while, but just as certain as a sultry Southern heat wave in September, they will always return.

–

About the Author: Shauna is an Upstate SC native and graduate of Converse College and ETSU. With a passion for both history and writing (and an advanced degree in Appalachian Studies that her parents SWORE she would never use,) she is excited to be able to share stories of the colorful people and places of the South. In her spare time, she enjoys archery, Rollerblading, and spending time aggravating her two teenagers with her endless stories.

About the Author: Shauna is an Upstate SC native and graduate of Converse College and ETSU. With a passion for both history and writing (and an advanced degree in Appalachian Studies that her parents SWORE she would never use,) she is excited to be able to share stories of the colorful people and places of the South. In her spare time, she enjoys archery, Rollerblading, and spending time aggravating her two teenagers with her endless stories.

Be the first to comment on "Murder in Muscadine Season; Fox Hunting (Part 3)"